Tobias Lock

LERU Brexit Seminar

In recent days, the option of an extended transition period has reportedly been floated by negotiators to break the deadlock in the Brexit negotiations. This blog post explores what such an extension could contribute, how it could be achieved in a way that is compatible with EU law and the political constraints of the parties, and how a provision providing for an extended transition period could be formulated.

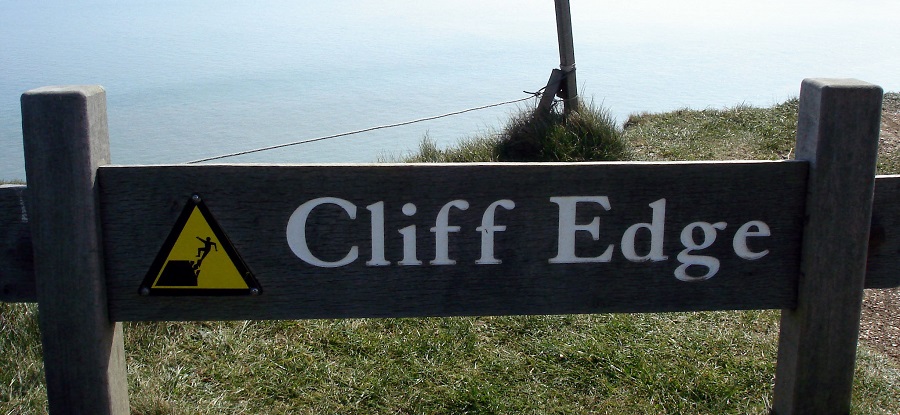

Photo credit: su-lin

Photo credit: su-lin

As is well known, the European Commission’s draft Withdrawal Agreement envisages a transition period starting on the day of the entry into force of the Withdrawal Agreement – likely 30 March 2019 – and ending on 31 December 2020. The purpose is to allow time for negotiations on the UK’s long-term relationship with the EU to be completed, notwithstanding that the UK will cease to be a member state on 30 March 2019. The transition period is, in effect, a standstill period, during which nearly all substantive provisions of EU law will continue to apply until the end of 2020.

While this provides some breathing space, it also implies that, if no long-term arrangement is agreed, the UK will, at the end of 2020, become in all respects a third state with trade and other forms of cooperation with the EU on the basis of international law rules (the so-called WTO model). This presents a second cliff edge which the Withdrawal Agreement cannot prevent since its provisions merely cover the modalities of leaving, and the accompanying political declaration on the long-term relationship is nothing more than a statement of intent.

An extended transition period is now being discussed to find a way around the problem of the Irish backstop. In their joint report of 8 December 2017, the EU and the UK agreed that there should be no hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland – meaning no physical infrastructure and no related checks and controls. The UK promised to be committed to attaining this objective resulting in the now famous Irish backstop, a draft version of which can be found in Annex I to the Withdrawal Agreement: it essentially provides that Northern Ireland remains in the EU customs union and in the single market for goods.

If this were agreed in the Withdrawal Agreement – and the EU insists that it is – there could potentially be a new customs and regulatory border between Northern Ireland and Great Britain, which is anathema to many unionists either side of the Irish Sea. Among the possible solutions – which could only be addressed in the agreement on a future relationship to be negotiated after Brexit day – are those that would keep the rest of the UK aligned with the EU single market in goods and in the customs union, but this would throw a spanner in the works of those wanting to pursue a truly independent UK trade policy; and technical solutions which would avoid physical border infrastructure and checks allowing Northern Ireland to be outside the EU’s regulatory space.

How would an extended transition help?

The answer is that it would merely buy more time and push the second cliff edge back. It is already obvious that the 21-month transition is extremely ambitious even if the end-result of the negotiations would only be a basic free trade agreement and security partnership. If on top a technically complex solution would have to be found that would both retain the Irish backstop in law and ensure that it would never have to be used in practice, the negotiators would come under even greater time-pressure making such an endeavor an almost impossible task.

Why agree an extension to transition now?

This is because the EU is legally constrained. There are serious legal doubts that an amendment to extend the transition period – introduced during transition – could be based on Article 50 TEU, which is the legal basis for the Withdrawal Agreement (and the transition period specified within it).

Article 50 does not empower the Union to conclude an agreement dealing with the future relationship between the EU and the UK. This means that an indefinitely renewable transition period would go well beyond the scope of Article 50 since it would have the effect of creating a new form of future relationship rather than an aspect of the withdrawal process. Thus the transition period must have a defined end date.

The main problem for a possible extension is that Article 50 TEU only allows for agreements to be concluded between the EU and a departing member state. Yet, once the Withdrawal Agreement is in force, the UK will have ceased to be a member state and Article 50 TEU would therefore no longer be applicable at that point. In the absence of an express extension clause in the Withdrawal Agreement, the EU would need to base an extension on a mix of other legal bases found throughout the EU Treaties; and in all likelihood that would not be enough either, so that it would be necessary to involve the Member States as well and conclude a so-called mixed agreement.

The disadvantage of that kind of arrangement is that it is procedurally cumbersome: not only must the EU ratify the agreement – usually by way of unanimity in the Council and consent of the European Parliament – but each of its 27 member states must do the same according to their respective constitutional requirements. This will in most cases involve a vote in the national parliament but may also require more, such as the consent of a regional parliament or even a referendum.

In recent years the Parliament of Wallonia voted against CETA, the EU’s free trade agreement with Canada, and the Dutch people rejected an act approving the EU’s association agreement with Ukraine in a referendum. Using a mixed agreement would thus make the ratification process – for which there may only be a short window in practice – subject to additional uncertainties such as challenges in national constitutional courts.

How could an extended transition be drafted in legal terms?

In a recent discussion paper for the European Policy Centre, Fabian Zuleeg and I therefore argue that the Withdrawal Agreement should include an express possibility for extending the transition period.

By including the express possibility of a time-limited extension of the transition period in the Withdrawal Agreement, both sides could avoid these issues.

This could be achieved by including the following draft clause into the agreement, which adds paragraphs 2 to 4, below, to Article 121 of the Withdrawal Agreement. That provision would then read as follows:

Article 121 Transition Period

1. There shall be a transition or implementation period, which shall start on the date of entry into force of this Agreement and end on 31 December 2020.

2. The initial transition period in paragraph 1 may be extended once for an additional period of one year at the request of the Union or the United Kingdom. The decision to extend the transition period may be taken by the European Council acting unanimously and in agreement with the United Kingdom. The decision to extend the transition period must be made before the end of the initial transition period and only after the procedure in paragraph 4 is completed.

3. During the additional transition period, Articles 122-126 shall apply in the same manner as during the initial transition period. During the additional transition period, the United Kingdom shall contribute to the Union’s budgets.

4. The request to extend the transition period must be communicated to the other party. Following this request, the European Commission shall produce a proposal containing estimates of the costs for the United Kingdom’s participation in Union policies and programmes during the additional transition period. On the basis of this proposal, the Council, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament, shall adopt a decision determining the United Kingdom’s financial contribution to the Union’s budgets for the additional transition period.

This clause could be based on Article 50 TEU provided it is included before the withdrawal agreement is ratified. It would ensure a one-off extension of one year bringing the total duration of the transition period to 33 months.

The extension procedure is fair on both sides: it requires the unanimous consent of the EU-27 (as represented in the European Council) and of the UK. This part of the clause is modelled on the procedure for extending the negotiating period under Article 50 TEU itself and thus prevents this provision from being circumvented. It also respects the transition period as originally envisaged in that neither side could be forced into an extension it did not want.

Furthermore, it ensures that both sides know precisely what the budgetary implications of the extension are. A clause like paragraph 4 is necessary because the EU’s current multiannual financial framework will expire on 31 December 2020 and the new framework will no longer assume that the UK is a member state. By stipulating that the decision to extend the transition period can only be made after the UK’s financial contribution for the additional period are clear, the EU-side could be certain it would not be left out of pocket by agreeing to an extension; and the UK-side would know the financial cost of extending transition, which would be an important factor for selling an extension politically in the UK.

Conclusion

Would the proposed clause avoid the second cliff-edge and resolve the Irish border conundrum? The answer depends very much on whether the treaty on the future relationship between the EU and the UK is agreed and how disruptive it will be for the EU-UK economic relations. The timeframe of 21 months for negotiating a relationship that – in the words of Donald Tusk – is ‘much further reaching on internal security and on foreign policy cooperation’ than CETA, which took eight years from the beginning of the negotiations until its provisional entry into force, is extremely tight. There is no guarantee that a deal can be reached, and the more ambitious such a deal is – cue the Irish border – the tighter the timeframe it will be. A one-off one-year extension of the negotiating period would therefore be a sensible insurance policy which might just give negotiators enough time to avoid a no-deal scenario and prevent the Irish backstop from kicking in.

Tobias Lock

Tobias Lock

University of Edinburgh

Dr Tobias Lock is Senior Lecturer in European Union Law and Co-Director of the Edinburgh Europa Institute at the University of Edinburgh. His research focuses on the EU’s multilevel relations with other legal orders, including the European Convention on Human Rights.

Shortlink: edin.ac/2NNMufJ | Republication guidance

Please note that this article represents the view of the author(s) alone and not European Futures, the Edinburgh Europa Institute or the University of Edinburgh.

This article is published under a Creative Commons (Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International) License

This article is published under a Creative Commons (Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International) License